Barrister turned crime writer offered readers a snapshot of 1920s life

|

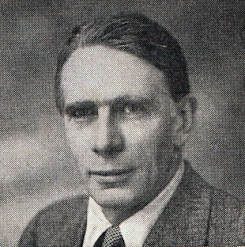

| C H B Kitchin, whose skill as a writer was only one of many talents |

Experts agree that one writer with a particular talent for evoking the era in which his stories were set is C H B Kitchin, a barrister who became wealthy from playing the stock market, and also tried his hand at detective fiction.

Born in October 1895, Clifford Henry Benn Kitchin was the son of a barrister who, after an Oxford education, became a barrister himself.

As well as being a gifted chess and bridge player and a pianist, Kitchin wrote poetry, general fiction and four highly-regarded crime novels featuring the stockbroker turned amateur sleuth, Malcolm Warren.

His first crime novel, Death of My Aunt, published in 1929, has been reprinted frequently and translated into several foreign languages. It was republished by Faber Finds in 2009, 80 years after its first appearance.

The novel introduces the young stockbroker, Malcolm Warren, who is summoned by telegram to visit his rich, old Aunt Catherine. She has recently shocked the family by marrying a muscular garage owner, who is many years her junior. She wants Warren to look at her investments and he is hopeful of being able to advise her on what to buy and to make a small profit for himself.

He hurries to her bedside, but before he can start discussing her investment book with her, his aunt asks him to pass her a new bottle of tonic that she wants to try. After taking a sip, she leans back and closes her eyes, but suddenly becomes violently ill and dies.

|

| The Faber Finds edition of Death of My Aunt |

Therefore, Warren has to launch his own investigation in order to save himself, and his uncle by marriage, who he likes and can’t believe is guilty of the murder.

Kitchin makes his hero, Warren, a fan of detective fiction himself and he mentions that he admires the crime writers Edgar Wallace and Lynn Brock. Warren tries to emulate Lyn Brock’s methods and draws up a table of suspects and motives and allocates each of them points for being the most likely person to have committed the murder.

In a later book, Death of His Uncle, Kitchin, through his hero Warren, says: ‘A good detective story, I have found, is often a clearer mirror of ordinary life than many a novel written specially to portray it. Indeed, I think a test of its goodness is the pleasure you can derive from it even though you know who the murderer is. A historian of the future will probably turn, not to blue books or statistics, but to detective stories, if he wished to study the manners of his age.

In 2021 we can be those historians and enjoy the fascinating domestic details and descriptions of servants, houses, furniture and dinners, which Kitchin, through Warren, reveals.

The writer H R F Keating writes in his Introduction to the 2009 edition of Death of My Aunt: ‘Kitchin’s knowledge of the crevices of human nature lifts his crime fiction out of the category of puzzledom and into the realm of the detective novel. He was, in short, ahead of his day.’

I would recommend Death of My Aunt to anyone who enjoys reading classic detective stories, as it is a well-written and interesting novel of its time, which provides a satisfying, credible solution to the mystery at the end.

Death of My Aunt is available from or