Remembering the novels of Monsignor Ronald Knox on the anniversary of his death

|

| Ronald Knox wrote books on many subjects as well as his detective novels |

The members of the Detection Club all agreed at the time to adhere to Knox’s Ten Commandments to give their readers a fair chance of guessing who is the guilty party.

During his career he produced the Knox Bible, a new English translation of the Latin Vulgate Bible, and many books on religion, philosophy and literature. Knox became a Roman Catholic chaplain at Oxford University in 1926 and was elevated to the title of Monsignor in 1936.

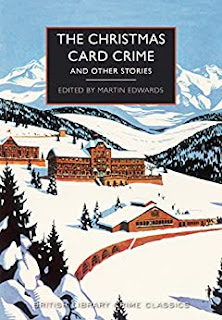

I was thrilled recently to discover a rare short story by Knox, The Motive, in a book of short stories edited by Martin Edwards for the British Library Crime Classics series. Some of these stories have never been republished since their first appearance in newspapers and magazines decades ago. I felt it was an opportune moment to write about The Motive as today is the 64th anniversary of Ronald Knox’s death.

In his introduction to the story, Edwards reveals that Knox had a passion for Sherlock Holmes stories and that this was what led him to try his hand at writing detective fiction. His first detective novel, The Viaduct Murder, appeared in 1925.

In The Christmas Card Crime, the third anthology of short stories for the British Library, Edwards introduces The Motive, which first appeared in The Illustrated London News in November 1937. Edwards writes: ‘Knox only wrote a handful of short crime stories but their quality makes this a matter for regret.’

|

| The Christmas Card Crime is a collection of short crime stories |

Sir Leonard counters by saying that if you are to succeed in the legal profession you have to be imaginative, rather than scientific, and offers to tell the group the story of one of his former clients, who was suspected of two murders, to illustrate this point. The dons all urge him to tell his story to prevent Penkridge becoming ‘unmannerly’.

The client is called Westmacott, which Edwards says Knox would have chosen for a joke because it was a pen name used by his Detection Club colleague Agatha Christie for her romance novels.

In just 16 pages, Knox manages to tell Westmacott’s unusual story, finishing with what Edwards describes as ‘a cheeky, if not shameless, final twist’ in the last paragraph. I found the story well worth reading and would definitely recommend it.

Knox first summarised his ‘fair play’ rules in the preface to Best Detective Stories 1928-29, which he edited. For budding detective novelists who would like to follow his Ten Commandments, or Decalogue, I reproduce them here:

1. The criminal must be mentioned in the early part of the story, but must not be anyone whose thoughts the reader has been allowed to know.

|

| Knox wrote his 'ten commandments' as a guide to fair play for detective writers |

3. Not more than one secret room or passage is allowable.

4. No hitherto undiscovered poisons may be used, nor any appliance which will need a long scientific explanation at the end.

5. No Chinaman must figure in the story.

6. No accident must ever help the detective, nor must he have an unaccountable intuition which proves to be right.

7. The detective himself must not commit the crime.

8. The detective is bound to declare any clues which he may discover.

9. The sidekick of the detective, the ‘Watson’, must not conceal from the reader any thoughts which pass through his mind, his intelligence must be slightly, but very slightly, below that of the average reader.

10. Twin brothers, and doubles generally, must not appear unless we have been duly prepared for them.

(As a matter of clarification, in the light of modern-day sensitivities, the reasoning behind rule number five is that magazine stories in the 1920s so often portrayed criminal masterminds as being of Chinese ethnicity that it had become something of a cliché, one that Knox believed was best avoided.)

According to Knox, a detective story ‘must have as its main interest the unravelling of a mystery, a mystery whose elements are clearly presented to the reader at an early stage in the proceedings, and whose nature is such as to arouse curiosity, a curiosity, which is gratified at the end.’

Knox himself wrote six detective novels: The Viaduct Murder (1926), The Three Taps (1927), The Footsteps at the Lock (1928), The Body in the Silo (1933), Still Dead (1934), Double Cross Purposes (1937).

He also contributed to three collaboration works by the Detection Club: Behind the Screen (1930), The Floating Admiral (1931) and Six Against the Yard (1936).

Paperback editions of all six of his detective novels were republished by the former Orion imprint The Murder Room in 2013.

The Christmas Card Crime and other stories, edited by Martin Edwards, was published by British Library Crime Classics in 2018.

No comments:

Post a Comment