Roman Catholic Monsignor lays down the ‘fair play’ rules for crime writers

|

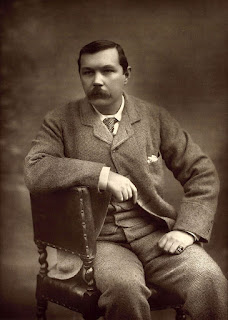

| Ronald Knox was a priest as well as a crime writer |

Knox

became a Roman Catholic priest and produced the Knox Bible, translating the

Latin Vulgate bible into English using Hebrew and Greek sources. He was also a

theologian, satirical writer and radio broadcaster.

The son

of a Church of England clergyman who became a bishop, Knox was educated at Eton

and Balliol College, Oxford.

He was

ordained an Anglican priest and appointed chaplain of Trinity College, Oxford.

During World War 1 he served in military intelligence.

When Knox

converted to Roman Catholicism, his father cut him out of his will. Knox

explained his conversion, which was partly influenced by the crime writer G K

Chesterton, by writing two books about it. When G K Chesterton also became a

Catholic he said he had been partly influenced by Ronald Knox.

After

Knox became a Catholic priest, he wrote and broadcast about Christianity and

other subjects. He became a Roman Catholic chaplain at Oxford University in

1926 and in 1936 was elevated to the title of Monsignor. He began writing

classic detective stories while a chaplain at Oxford.

This was

during what is now referred to as the Golden Age of Detective Fiction in the

1920s and 1930s and Knox was one of the founding members of the Detection Club.

|

| A picture taken at a 1932 meeting of the Detection Club, when G K Chesterton was president |

The

members of the Detection Club agreed to adhere to Knox’s Commandments in their

writing to give the reader a fair chance of guessing who was the guilty party.

These

‘fair play’ rules were summarised by Knox in the preface to Best Detective

Stories 1928-29, which he edited.

Knox’s

Ten Commandments, or Decalogue, are as follows:

1. The criminal must be mentioned in the early part of the story, but must not be anyone whose thoughts the reader has been allowed to know.

2. All

supernatural or preternatural agencies are ruled out as a matter of course.

3. Not

more than one secret room or passage is allowable.

4. No

hitherto undiscovered poisons may be used, nor any appliance which will need a

long scientific explanation at the end.

5. No

Chinaman must figure in the story.

6. No

accident must ever help the detective, nor must he have an unaccountable

intuition which proves to be right.

7. The

detective himself must not commit the crime.

8. The

detective is bound to declare any clues which he may discover.

9. The

sidekick of the detective, the Watson, must not conceal from the reader any

thoughts which pass through his mind, his intelligence must be slightly, but

very slightly, below that of the average reader.

10. Twin

brothers, and doubles generally, must not appear unless we have been duly

prepared for them.

According to Knox, a detective story ‘must have as its main interest the unravelling of a mystery, a mystery whose elements are clearly presented to the reader at an early stage in the proceedings, and whose nature is such as to arouse curiosity, a curiosity, which is gratified at the end.’

|

| The Murder Room's edition of Knox's first detective novel |

Knox was a prolific satirical writer and wrote many essays and books about religion.

He also

wrote some crime short stories and six detective novels: The Viaduct Murder

(1926), The Three Taps (1927), The Footsteps at the Lock (1928), The Body in

the Silo (1933), Still Dead (1934), Double Cross Purposes (1937).

Paperback editions of all six detective novels were published by the former Orion imprint The Murder Room in 2013 and are still available from Amazon and Waterstones.

He also

contributed to three collaboration works by the Detection Club; Behind the

Screen (1930), The Floating Admiral (1931) and Six Against the Yard (1936).