Dorothy’s dazzling debut detective novel

Having read the first crime novel by Agatha Christie, The Mysterious Affair at Styles, published in 1920, and the first by Margery Allingham, The Crime at Black Dudley, published in 1929, I thought it was only fair to turn my attention to the first novel by Dorothy L. Sayers, the third Englishwoman who was dubbed a Queen of Crime.

Dorothy began writing her first crime novel, Whose Body? in 1920, at the beginning of what has been called the Golden Age of detective fiction, which lasted from 1920 until the start of World War II.

|

| A 2016 copy of the 1923 novel. |

I am a big fan of Dorothy L Sayers

and I have read and enjoyed most of her Lord Peter Wimsey novels and short

stories. Or, at least I thought I had. But reading her novels purely for

pleasure many years ago meant that I had not read them in any particular order

and therefore I had somehow missed out on Whose Body?, her first novel.

Used to the Wimsey of the later

novels, I found him a bit irritating to begin with, his dialogue making him

sound more like Bertie Wooster than the highly intelligent and perceptive

amateur sleuth he was to become. However, as the book progresses, he is

gradually revealed to be a kind and sensitive person, who has developed an

interest in criminal investigation as a hobby, but is still suffering from the

trauma of his experiences during the First World War. He experiences flashbacks and hears the terrifying sound of the guns when he is placed under a lot of pressure.

It is his mother, the Dowager Duchess

of Denver, who presents him with his first case. Mr Thipps, the architect

working on her local church, has just discovered the corpse of a man,

completely naked apart from a pair of gold pince-nez, lying in the bath at his

Battersea flat.

Wimsey gets round there before the

corpse is taken away and, much to the irritation of the police officer in

charge of the case, he manages to assess the crime scene for himself.

Thipps is completely shocked by the

discovery and is then arrested for the murder of the man, so Wimsey sets out to

try to find out who the naked corpse was and who put him in the bath of Mr

Thipps, wearing only a handsome pair of gold pince-nez.

By the time I got to the end of the

novel I was once again in awe of Dorothy’s writing, her brilliant plotting, her

clever use of dialogue to present facts and the skilful way she shows Wimsey

unravelling the mystery for the reader.

I was also struck by the differences

between Dorothy’s debut novel and the first novels of Agatha Christie and

Margery Allingham.

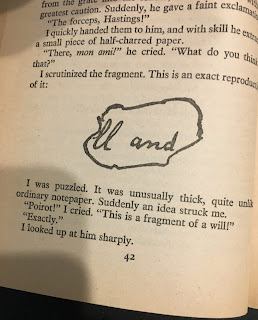

Agatha used a country house setting

for her murder, with a closed circle of suspects, and the clues involved

alibis, overheard conversations and dressing up in disguise.

Margery also used a country house,

but her first crime novel was less of a murder mystery with a crime to be

solved, but more of a suspense novel, with a criminal gang taking over the country house after an old man is found dead, with the reader left wondering whether the good

guys will triumph over the bad guys by the end of the book

Dorothy L Sayers created

Lord Peter Wimsey

Dorothy sets her story in London, with

many of the scenes taking place in Wimsey’s Piccadilly flat.

Wimsey, helped by his manservant,

Bunter, uses forensic techniques such as finger printing and examining minute

pieces of evidence through a magnifying glass, before carefully arriving at his

conclusions.

The novel does not involve a closed

circle of suspects as the action takes place in various people’s homes, in a

hospital, a workhouse, and also involves a trip to Salisbury. When Wimsey

finally solves the puzzle he is overcome with revulsion about what will happen

to the murderer, revealing another intriguing aspect of his character.

Whose Body? was acclaimed as a

stunning first novel by reviewers and Dorothy was described as a new star in

the firmament. The only criticism was that she made Lord Peter seem too

fatuous, but she soon toned this down.

Sayers herself said of her creation

of Wimsey: ‘At the time I was particularly hard up and it gave me pleasure to

spend his fortune for him. When I was dissatisfied with my single, unfurnished

room I took a luxurious flat for him in Piccadilly… I can heartily recommend

this inexpensive way of furnishing to all who are discontented with their

incomes.’

Whose Body? is available in a variety of formats from Amazon.