First appearance by author turned sleuth Roger Sheringham

|

| The paperback edition of The Layton Court Mystery |

His series

detective, Roger Sheringham, is one of the guests at a country house party being held at a Jacobean

mansion called Layton Court. The character, who is an author, was to feature in another ten detective novels

and many short stories by Berkeley.

The party is being hosted by Victor Stanworth, a genial and hospitable man, aged

about 60, who has taken Layton Court for the summer to enable him to entertain

his friends in style.

At the start

of the book, Sheringham has been enjoying Stanworth’s generous hospitality for

three days until the party is given the grim news during breakfast that their

host appeared to have locked himself in the library and shot himself.

Sheringham

is not convinced that his host has committed suicide and sets out to

investigate the mystery himself, using his friend, Alec Grierson, who is also

in the party, as his ‘Watson’.

Anthony

Berkeley was just one of the pen names used by Anthony Berkeley Cox, who died

51 years ago today (9 March 1971). He also wrote novels under the names Francis

Iles and A. Monmouth Platts.

Anthony

Berkeley Cox helped found the Detection Club in 1930, along with Agatha

Christie and Dorothy L Sayers. It was to become an elite dining club for

British mystery writers, which met in London, under the presidency of G. K.

Chesterton. There was an initiation ritual and an oath had to be sworn by new

members promising not to rely on Divine Revelation, Feminine Intuition, Mumbo

Jumbo, Jiggery Pokery, Coincidence or Act of God in their work.

|

| Berkeley Cox wrote 19 crime novels before returning to journalism |

I found The

Layton Court Mystery unexciting and stilted at the beginning, but the writing improved

a lot as the book progressed.

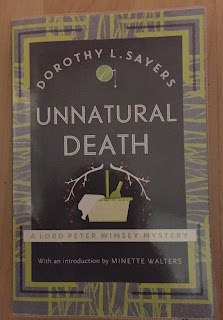

I thought Roger

Sheringham had the potential to be a good character, although some of the rather

fatuous dialogue at the beginning reminded me of Lord Peter Wimsey at the

start of Whose Body? the first novel by

Dorothy L Sayers that he appeared in.

Sheringham

sometimes tells Grierson what detectives in books would do in particular

circumstances, showing that the character, like his creator Berkeley, is a

devotee of the genre.

The amateur

detective jumps to a few wrong conclusions along the way and

follows up each of his theories until he accepts that they are disproved. He

tells the other characters that he is asking questions because he has ‘natural

curiosity’, to cover up the fact he is interrogating people he doesn’t really

know, which was not considered good form at the time.

He sometimes

says he is looking for material for his next novel and one of the characters

actually says to him: ‘Everything’s “copy” to you, you mean?’

He also

finds clues, such as a footprint, a hair, a piece of a broken vase and a trace

of face powder, to help him work out what has taken place in the library.

|

| The Poisoned Chocolates Case sold more than a million copies |

He wrote 19

crime novels between 1925 and 1939 before returning to journalism and writing

for the Daily Telegraph and the Sunday Times. From 1950 to 1970, the year

before he died, he contributed to the Manchester Guardian, later, the Guardian

newspaper.

Berkeley’s

amateur detective, Sheringham, had his most famous outing in The Poisoned

Chocolates Case, which was published in 1929. The novel received rapturous

reviews and sold more than one million copies. It is now regarded as a classic

of the Golden Age of detective fiction.

At times, The

Layton Court Mystery reminded me of Trent’s Last Case by E C Bentley, published in 1913, which was

originally intended to be a skit on the detective story genre. Like Trent,

Sheringham doesn’t actually solve the case until the real murderer confesses to

him right at the end.

However, by

the end of The Layton Court Mystery, I had taken to Roger Sheringham and I now look

forward to reading the next book in the series.

The Layton Court Mystery was first published in London by Herbert Jenkins in 1925 and in New York by Doubleday, Doran and Company in 1929. It was republished by Spitfire Publications Ltd in 2021.

Anthony Berkeley's books are available from and