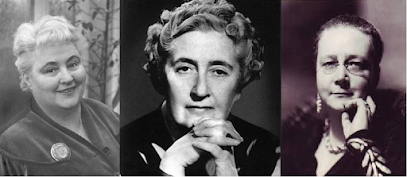

Dorothy turns Lord Peter into a man of action as well as words

The second Dorothy L Sayers novel featuring amateur detective Lord Peter Wimsey was nothing if not ambitious.

|

| The second Lord Peter Wimsey novel by Dorothy L Sayers |

The action took place in Yorkshire, London, Paris and the US and the denouement sees a Duke being tried for murder by his peers in the House of Lords.

This is a far cry from the country house murder with a closed circle of suspects that was all the rage in 1926, the year Clouds of Witness was published.Reading it for the second time, many

years after I had first read the novel, I was more impressed with it than ever.

The plot is brilliant and intricately

worked out, considering that the action takes place over such a large canvas.

Peter’s brother, Gerald, Duke of

Denver is hosting a shooting party at a lodge in Yorkshire. His sister, Lady

Mary Wimsey, is acting as the hostess for her brother and her fiancé, Captain

Denis Cathcart, is one of the guests.

Denis Cathcart is found just outside

the conservatory in the early hours of the morning having been shot dead by a

bullet fired from the Duke’s revolver. The Duke is bending over his body when

Lady Mary arrives on the scene. An inquest into Cathcart’s death is later told

that Lady Mary exclaimed: ‘Oh God, Gerald, you’ve killed him!’

Needless to say, the Duke of Denver

is later arrested for the murder of his future brother in law. He refuses to

say why he was up and about at the time he discovered the body and Lady Mary

feigns illness to avoid have to talk to anyone about it at all.

Lord Peter and his manservant,

Bunter, waste no time in returning from their holiday in France to assist the

investigation and they set out to try to prove the Duke’s innocence.

And what could be more convenient

than Peter’s friend, Inspector Parker, being assigned to the case by Scotland

Yard?

|

| Ian Carmichael played Lord Peter Wimsey in a BBC TV adaptation of Clouds of Witness |

P D James, in her excellent book

Talking about Detective Fiction, says she was amused by the plan of the layout

of Riddlesdale Lodge that Dorothy provides for the reader, pointing out that

just one toilet and one bathroom shared by eight unrelated people must have

been rather inconvenient.

The action ranges across the

surrounding moorland, a farmhouse inhabited by a violent farmer and his

beautiful wife, and a nearby market town. Cathcart also had a life in Paris

that has to be investigated.

The Dowager Duchess of Denver arrives

at the lodge to deal with Lady Mary. We were introduced to her in Whose Body?

but in the second novel she is more entertaining than ever. She has long

soliloquies that move from subject to subject as one thought leads her

to another, but there is somehow a strange logic in what she says. She also

provides what she refers to as her ‘mother wit’ to aid the investigation.

The inquiries in Paris, events in

London and further adventures in Yorkshire bring Lord Peter and Parker closer

to the truth.

|

| Sayers's second Lord Peter Wimsey novel saw her character become more an action man |

The crime writer Martin Edwards has

suggested that Clouds of Witness is the work of a novelist learning her craft

but that it displays the storytelling qualities that soon made her famous.

I agree with this in part. I feel

that Dorothy made large passages of the dialogue difficult to read by trying to

reproduce the Yorkshire accent in print when Lord Peter is interviewing locals

such as pub landlords and farmers.

She also allowed Lord Peter to

chatter too much at the beginning of the book when he and Parker are sleuthing

together. In real life the more ordinary detective inspector would probably

have begun to find his inane conversation rather trying.

But she allows Lord Peter to become

much more of a man of action than she did in her first novel, more along the

lines of Margery Allingham’s Campion than Agatha Christie’s Poirot. Lord Peter

is sucked into a bog while roaming over the moors at night and has to be

rescued by Bunter with the help of some local labourers and he is shot and

injured while chasing a suspect in London.

Near the end Lord Peter has to make a

last minute dash to New York to secure a final piece of evidence to exonerate

the Duke, which will reveal the truth about Cathcart’s death.

To be in time to present his evidence

at the trial in the House of Lords he has to make a daring and dangerous flight

back to London.

The Duke’s defence counsel, Sir Impey

Biggs, explains to the court how Lord Peter is making a transatlantic dash to

return before the end of the trial: ‘My Lords, at this moment this

all-important witness is cleaving the air high above the wide Atlantic. In this

wintry weather he is braving a peril which would appal any heart but his own

and that of the world-famous aviator whose help he has enlisted, so that no

moment may be lost in freeing his noble brother from this terrible charge. My

lords, the barometer is falling.’

Lord Peter’s fictional flight was

described in a novel published in 1926, a year before Charles Lindbergh was to

achieve the same feat in reality.

The amateur detective arrives at the

House of Lords looking ‘a very grubby and oily figure’ and presents the vital

evidence that will exonerate his brother.

He also provides a satisfying

conclusion to the mystery for the reader, which is one of the key ingredients

of any crime novel.

Clouds of Witness is available in a variety of formats from or