How the genre of detective fiction originated

|

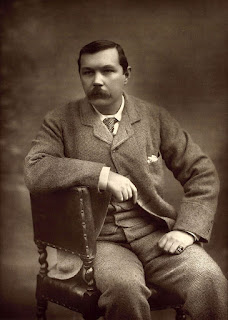

| Sir Arthur Conan Doyle began writing mysteries in the 1880s |

One of

the four Golden Age Queens of Crime, Dorothy L Sayers, once wrote: ‘Death in

particular seems to provide the minds of the Anglo-Saxon race with a greater

fund of innocent amusement than any other single subject.’ She was writing in

the preface to a volume of detective stories published in 1934.

By then,

ingenious stories of crime and detection had become really popular and she was

one of the most well regarded writers of these novels in Britain.

Most

people know the name Sherlock Holmes, a fictional detective who featured in the

novels of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, even if they have never read any of the

stories themselves.

Sir

Arthur began writing mysteries featuring Sherlock Homes and Dr Watson in the

early 1880s but they are still popular today and are constantly being reissued

and made into new TV and film adaptations.

As

someone who loves cosy crime and has even had a go at writing novels in the

cosy crime genre, I am fascinated with reading the books that came before.

And so I

began to wonder where Sir Arthur got his ideas from. For me, it is not a case

of whodunnit, but of who started it?

|

| Did Wilkie Collins write the first English detective story? |

The

author Wilkie Collins, who was a friend of Dickens, wrote a novel that is often

referred to as the first English detective story, The Moonstone. At the time,

books by Wilkie Collins were classified as sensation novels, but this category

is now thought to be a precursor to detective and suspense fiction.

The

Moonstone, published in 1868, was later described by T S Eliot as ‘the first,

the longest and the best of modern English detective novels’.

Dorothy L

Sayers has referred to The Moonstone as ‘probably the very finest detective

story ever written.’

The

Moonstone referred to in the title of the story is an Indian diamond that has

been inherited by a young English woman. The diamond is of great religious

significance and is highly valuable. The woman wears the Moonstone on her dress

for her 18th birthday celebrations, but later that night it is stolen from her

bedroom. The complex plot of the book follows the attempts to explain the

theft, identify the thief, trace the stone and recover it.

The novel

introduces a number of elements that were later were to become essential

components of the classic English detective novel, such as an English country

house setting, red herrings, a celebrated investigator, bungling police, the

least likely suspect and a final twist in the plot.

|

| William Godwin's Caleb Williams |

Also

known as Things As They Are, or The Adventures of Caleb Williams, Godwin’s

story was published in the form of a three volume novel. It was written as a

call to end the abuse of power by what he saw as a tyrannical government. But

it involves a man being falsely accused of crimes and desperately trying to

seek justice. The novel has an amateur detective as a character and, at its

core, is a murder, for which two innocent men have been hanged.

However,

P D James concludes in her 2009 book, Talking About Detective Fiction, that if

she had to award the distinction of being the first English detective novel,

her final choice would be The Moonstone, as it most clearly demonstrates what

were to become some of the main characteristics of the genre. Also, in

the rose growing detective, Sergeant Cuff, Wilkie Collins created one of the

earliest, fictional professional detectives.

Both Caleb Williams and The Moonstone are available in a variety of formats.