As someone who loves Italy and likes to travel there as often as possible, I have been disappointed - as have millions of others - about having to cancel my planned trip there later this month.

But these are unprecedented times and this global pandemic has wreaked havoc in people’s lives in many different ways. I consider myself lucky that the only deprivation I am suffering is not seeing my friends and extended family.

|

Venice is the setting for Donna Leon's Italian crime novels.

(Photo by Pixabay on Pexels.com) |

But one benefit lockdown has given us all, is more time to read and the next best thing to going to Italy is reading about it.

I enjoy reading crime fiction and over the years it has been a real treat to discover good crime novels set in interesting locations in Italy.

Among my favourite authors whose crime novels are in English and set in Italy are Michael Dibdin, Donna Leon, Timothy Holme and Magdalen Nabb.

But thanks to good translators, we are also now able to read the works of Italian crime writers.

The Sicilian writer Andrea Camilleri is perhaps the most famous and one of my favourites, but I have also enjoyed discovering the works of Michele Giuttari, Valerio Varesi and Marco Vichi to name but a few. It is always a joy to discover less well-known writers, as well as writers not normally known for books set in Italy, who have chosen to use the country as a backdrop for just one novel.

The range of crime novels set in Italy and the variety of locations they feature is constantly increasing.

Translations of crime novels by Italian writers are now much more readily available, for the first time making these books accessible to people who can’t read Italian, so we suddenly have an exciting and rapidly growing sub genre of crime fiction.

Andrea Camilleri’s Montalbano series set in Sicily has now been translated into 30 different languages and a dubbed version of the television adaptation has been shown on British television, which has helped to increase the interest in and demand for crime novels with an Italian setting.

What makes Italy a good setting for the genre?

Reading crime novels in translation is fascinating for us because it offers us a window on day-to-day life in Italy, enabling us to see how people spend their time and what their preoccupations are as well as what wine they choose when they go to their local bar.

It has made me wonder why Italy makes such a good setting for this genre.

I like Italy for the weather, the scenery, the architecture, the art, the culture and let’s not forget the food and the wine.

|

Italy is renowned for its beautiful scenery.

(Photo by Aliona & Pasha on Pexels.com) |

But a good crime novel set in Italy should be more than just an opportunity for armchair travel by the reader. The setting has to play an important part in the novel.

A lot of writers are fascinated with Italy’s justice system and the much talked about corruption in the country because it can give them more freedom when they are plotting their novels.

Italy provides writers with the opportunity for ambiguity and non-resolution at the end of the book, whereas readers have come to expect a credible, tidy finish at the end of a book set in Britain. For example, Agatha Christie and Dorothy L Sayers often used to allude to the fact that the murderer would hang at the end of their books because at the time they were written they thought this would provide a satisfactory resolution for the reader.

But there is often no neat conclusion at the end of a crime novel set in Italy. Andrea Camilleri has said that in Italy it can take years to find someone guilty of a crime and then there is often no appropriate punishment at the end of it all. Italians are big believers in hidden and ulterior motives and even when someone is arrested for a crime they think this won’t necessarily be the end of it. I came across the word dietrologia for the first time in a Michael Dibdin novel. It means the facts behind the facts, or conspiracy theory, and it is something Italians have no difficulty believing in.

This makes Italy an ideal background for modern writers who want to make the investigation of lesser importance and concentrate more on the personalities of the victim, witnesses and investigators that they have created.

Italian crime writers love an outsider

The perspective of the outsider is a popular device in crime fiction and so having a foreign visitor in Italy as a central character often works well. It enables the protagonist to cast a cold eye on the society that surrounds him and his detachment is often the key to his success. This can also work well if the character is Italian. For example with Commissario Aurelio Zen in Michael Dibdin’s novels there is a reason he feels like an outsider in Rome, which the reader eventually finds out about.

In some novels Italian police officers are working far away from their home town for operational reasons, such as Magdalen Nabb’s Maresciallo Guarnaccia, a Sicilian in Florence and Timothy Holme’s Commissario Peroni, a Neapolitan in northern Italy.

|

Magdalen Nabb's novels feature a Sicilian

policeman in Florence.

(Photo by Alex Zhernovyi on Pexels.com) |

Modern crime novelists have almost become travel writers, because they describe their settings so well. This is because to the writer the location is a character in the story in its own right.

At the very least a modern crime novel set in Italy can take you on a trip to an unfamiliar city. Crime writers tell it the way it is. Unlike most travel writers they will tell you things you didn’t know and maybe would prefer not to know about a particular place.

They will tell you about day-to-day life, what people talk about in the bars, how the place smells, how the transport system works, or doesn’t work, in some cases.

If you are lucky, as a little bonus, they will also tell you what dishes to order for lunch and the best restaurants to go to for an authentic experience of the local cuisine, as in Donna Leon’s Commissario Brunetti novels set in Venice.

But good crime writers do not forget the rules of the genre and that plot is of paramount importance.

Readers expect to be provided with clues, suspects, and motives. They want to be entertained by a story that allows them to sit in an armchair and try to work out the solution. The characters have to be plausible and their motivation for what they do needs to be credible.

Most of all, the book needs to have an authentic background that the reader can believe in, which is why the use of the setting is so important.

The origins of crime fiction

The crime, or detective, novel dates back to the mid-19th century. One of the earliest detective novels, The Murders in the Rue Morgue by Edgar Allen Poe, was published in 1841 and then Wilkie Collins wrote The Woman in White in 1860.

In 1887 Sir Arthur Conan Doyle gave the genre fresh impetus by creating Sherlock Holmes. His skill in detection consisted of logical deduction based on minute details that have escaped the notice of others.

The classical detective novel was at the height of its popularity in Britain between about 1920 and 1940, the era of four famous women writers, Agatha Christie, Dorothy L Sayers, Margery Allingham and Ngaio Marsh.

Their novels provided entertainment that relied upon the reader’s interest in a logical pursuit of clues honestly put before them.

Books by these ladies are still regularly borrowed from public libraries and made into films and yet publishers and literary critics consistently try to claim that this form of the genre has had its day.

The contemporary crime novel, or detective novel, shifts the emphasis from the clues to the characters involved in the story. It is the unveiling of the different layers of personality that lies at the root of the plot rather than just logical deduction.

The personality of the detective is a vital ingredient as it is he or she whose insights produce the solution to the puzzle.

Writers who achieved this transition include P D James, Ruth Rendell, H R F Keating, Colin Dexter and Reginald Hill.

|

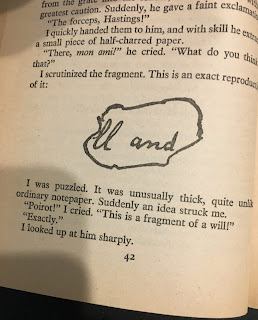

Crime novels in Italy are known as gialli because

they traditionally had yellow covers |

Their books are more likely to involve professional policemen, who carry out thorough detective work rather than just relying on sudden flashes of intuition,

In Italy, people call a crime story un romanzo giallo, because since the 1930s crime novels usually had yellow covers, giallo being the Italian for yellow.

The earliest Italian mystery novels are thought to be Il Mio Cadavere (My Corpse) and La Cieca di Sorrento (The Blind Woman from Sorrento) both written by Francesco Mastriani in 1852.

Other Italian writers then began experimenting with the genre and in 1910 there was an important development when The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes were published in Il Corriere della Sera, the Milan newspaper.

In 1929, publishers Mondadori established their libri gialli series and novels by famous foreign writers, including Agatha Christie, were published in Italian. The first Italian writer to be published in the series was Alessandro Varaldo with Il Sette Bello (Seven is Beautiful) in 1931 featuring police inspector Ascanio Bonich. This is considered to be the first Italian detective story.

The fascist Government asked Mondadori to ensure that at least 20 per cent of its literary production was by Italian writers and as a result more Italians started to write gialli and to imitate foreign authors.

But by 1941 Mussolini had decided he didn’t like the genre and told Mondadori to stop publishing gialli for moral reasons. He thought they would corrupt young people.

After the war Mondadori began publishing foreign writers again, but gradually more Italian crime writers began to emerge and now hundreds of Italian crime writers are regularly published, including best selling novelists such as Andrea Camilleri. Sadly, he died last year, but he has left us the wonderful gift of Montalbano, who, like Sherlock Holmes, often notices the little details that other people miss.

Home